When reading about psychology it can often be a challenge to understand what all the different terms mean. It can seem like a lot of jargon at times and this can make it difficult to unravel what everyone is actually talking about when discussing the brain and its mysterious inner workings.

One of the terms that you will hear most commonly and that is most fundamental to an understanding of the brain and psychology is ‘neurotransmitters’. Here we will take a look at what this word means and at what neurotransmitters actually are.

The Role of Neurotransmitters

Basically, neurotransmitters are chemicals in the brain that are similar to hormones. In fact, some hormones double as neurotransmitters. Norepinephrine for instance is essentially just another term for noradrenaline that is used to describe the effects that it has on the brain. Likewise epinephrine is essentially adrenaline.

Like hormones, neurotransmitters have a big effect on emotion but they also control our mental states and regulate things like hunger, learning and tiredness. They can increase or decrease neuronal activity, either at a specific region in the brain or throughout it.

How Neurotransmitters Work

The brain can be imagined as essentially being a large interconnected web of neurons. These neurons represent our ideas, experiences and memories and when they fire (through small electrical impulses) this impacts the way we feel. If some neurons light up it might cause us to feel pain in a certain part of our body. Another set of neurons might represent a memory and another might cause us to see something.

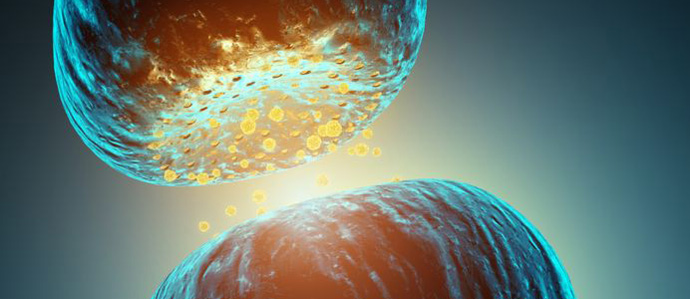

Neurotransmitters communicate via electrical signals called ‘action potentials’ and this causes small amounts of electrical charge to jump across the gap between two neurons (the synapse). But it’s not just a charge that travels across this chasm – at the same time neurotransmitters are released from the end of one neuron and will then land on the end of the other. These neurotransmitters are held in little ‘sacks’ called microvesicles and when the charge fires they are released in order to travel to the end of the other neuron. Here they will then fit into ‘receptors’.

What’s important to note is that receptors can only receive specific neurotransmitters or chemicals that have a similar structure. For instance, you have GABA receptors called GABAa and these are only affected by GABA. Likewise A1 receptors receive adenosine (and caffeine actually) but not GABA. This means that certain brain areas will only respond to certain neurotransmitters.

Examples

When these neurotransmitters are received during the action potential, they essentially have the effect of adding some context to what just happened. Let’s say for instance that you saw a box of treasure. Now if you thought that box of treasure was fake then you might be unimpressed and thus the signal might fire without much other activity. However, if you thought that treasure chest was real and probably full of gold, the dopamine might be released and this in turn would cause you to be more likely to remember its location, to be more likely to remember seeing it and to pay more attention and feel more alert in that moment.

Similarly, if you were to see a lion, then this would create a ‘fight or flight’ response and that would be characterized by the release of norepinephrine – which as you remember is essentially adrenaline and has the same effect of making you feel terrified.

Other neurotransmitters work in slightly different ways and have different effects. Adenosine for instance is a neurotransmitter that is a waste product of brain activity and which builds up throughout the course of the day. This then makes you feel tired and causes brain fog and eventually makes you sleep. Likewise melatonin also makes you feel tired and is regulated by the light – when it gets dark the brain releases melatonin which suppresses activity. GABA is the main ‘inhibitory’ neurotransmitter and generally reduces activity across the entire brain again helping you to sleep and having something of a sedative effect.

Other neurotransmitters like serotonin and oxytocin make us feel love and euphoria. Others, like ghrelin make us feel hungry. All of them are released by the brain, attach themselves to receptors and alter our perception of the stimuli we are receiving/experiencing.

Variations in Neurotransmitters

When neurotransmitters are working well they are highly effective in regulating our behavior and in helping us to focus at the right times, to relax at the right times and to generally feel calm, happy and focused by default. But sometimes neurotransmitters go wrong and this can result in all kinds of negative effects and mental health problems. Conditions like psychopathy, insomnia, depression and others can all often be explained – at least partially – by imbalances of neurotransmitters.

This then is why many psychiatric medicines work by trying to increase or decrease the action of certain neurotransmitters. These include precursors which the body uses in order to make more of particular neurotransmitters, reuptake inhibitors which block receptors and thus increase the amount of a certain neurotransmitter available and a range of other substances that each increase or decrease the performance of particular neurotransmitters in a variety of ways.

The problem though is that the brain can adapt to drug use and will do so by producing less of that specific neurotransmitter naturally, or by increasing or decreasing the number of receptors. This is called ‘dependence’ or ‘tolerance’ and it is one of the mechanisms for drug addiction.

The question then, is whether manipulating neurotransmitters actually offers a safe and healthy way to impact brain states and mood etc., or whether it would better to use a bottom-up approach and to look at how our thoughts regulate the production of these transmitters and how we can thereby alter our thinking patterns in order to control the release and use of these substances. Should you change the thinking in order to affect the neurotransmitters, or should you change the neurotransmitters in order to alter the thinking? And is there a third option that offers the best of both worlds? This is one of the biggest questions surrounding psychology.

Another time when neurotransmitters are ‘atypical’ is when they are altered by recreational drug use. Recreational drugs often stimulate the neurotransmitters associated with reward and pleasure and this gives the user feelings of euphoria and reinforces their behavior making the user want to use them more often. This combined with dependence and tolerance makes them even more highly addictive.

Finally neurotransmitters might also be altered by some supplements and ‘smart drugs’ in an attempt to change our brain states to become more focused, alert and productive. The most common example of this is our use of caffeine in order to feel more awake (by reducing adenosine) and to become more focused and productive. Others will use other more potent drugs to try and achieve the same effects.

Ultimately though, it’s important to understand that neurotransmitters don’t work in a vacuum. You can’t change one without impacting all the others and there are some we don’t even know about yet. While we understand a lot about neurotransmitters now then, we aren’t close to understanding enough to manipulate them in this way.