Freudian Psychoanalysis is not a set of theories developed by a psychology professor in some Oxford or Harvard University library. Freud was a medical doctor and neurologist who sought to relieve neurotic patients of their obsessions, anxieties and depression. In other words, he developed his ideas based on his experiences with patients. And he left behind some remarkable descriptions of these encounters, known as his ‘case studies’. Freud was a gifted writer and these studies, far from dry and clinical, often seem more like bizarre, macabre short stories.

The Case Studies

Of course, Freud is not the only person to have published such case studies. In 1941, for example, the American psychiatrist Hervey Cleckley published his classic Mask of Sanity, a dramatic and novelistic description of the psychopathic individuals he met in an institution for the criminally insane. The British psychiatrist R.D. Laing also published a collection of case studies under the title Sanity, Madness and the Family. Laing interviewed the parents of young schizophrenics, mostly in and around London, to show how mental illness can be triggered by life in a dysfunctional family.

When reading Freud’s studies, the reader is immediately struck by the astonishing complexity of a neurotic illness. And this complexity may explain why Freud wrote up so few case histories. Over the whole of his career, he only published five of real depth and significance, and all were written before the First World War.

Anna O

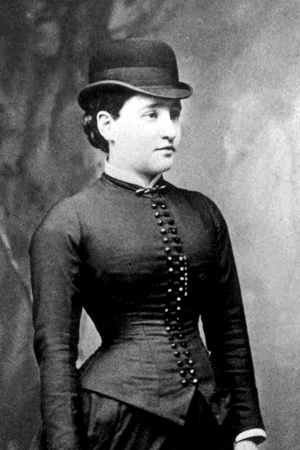

Anna O is often described as Freud’s first case study. In fact, she was not really his patient at all but that of a colleague, Josef Breuer, with whom Freud wrote Studies on Hysteria, a collaborative work in which her case is presented. Anna was a pseudonym for Bertha Pappenheim, a 21-year-old Jewish girl who first visited Breuer in 1880. Her symptoms included a severe cough, hallucinations, disturbed vision and hearing, and paralysis of the right side of the body. Anna had been brought up in a very strict household and was sexually ignorant and immature. She had nursed her father through a terminal illness and, after his death, her symptoms grew worse.

Anna O is often described as Freud’s first case study. In fact, she was not really his patient at all but that of a colleague, Josef Breuer, with whom Freud wrote Studies on Hysteria, a collaborative work in which her case is presented. Anna was a pseudonym for Bertha Pappenheim, a 21-year-old Jewish girl who first visited Breuer in 1880. Her symptoms included a severe cough, hallucinations, disturbed vision and hearing, and paralysis of the right side of the body. Anna had been brought up in a very strict household and was sexually ignorant and immature. She had nursed her father through a terminal illness and, after his death, her symptoms grew worse.

During the day, she experienced hallucinations and at night fell into a trance and mumbled to herself. Breuer found that by encouraging her to describe these hallucinations and say aloud the words she normally mumbled, he could bring her some relief. Later, she developed a fear of water and was unable to drink for days at a time. During one of her trances, she recalled watching an English tourist allow her dog to drink water from a glass. After she had described this sight and released the emotion connected to it (in this case disgust), she was able to drink once more. Again and again Breuer found that by tracing a symptom back to its source it could be removed. For example, Anna had wanted to cry while sitting by her father, but she thought her tears would disturb him. And when she wanted to check the time, she had to squint. This had led to her impaired vision. The paralysis was traced once again to her father’s bedside. One night she had seen a black snake. Obviously, she couldn’t scream because it would have upset and frightened her father. She was so afraid that the right side of her body seemed to go numb, and she found that she couldn’t move her right arm.

Dora

Dora, whose real name was Ida Bauer, was 18 when her father first brought her to see Freud. Like Anna O, she was diagnosed as hysteric. In Dora’s case, however, she seems to have suffered with hysterical symptoms since childhood.

Like Anna, Dora suffered from multiple symptoms, including migraines, depression, breathing difficulties, nervous cough, and inexplicable voice loss. Her parents were unhappily married and her father had begun an affair with the wife of a close friend (whom Freud names Mrs K). The husband (Mr K) had made sexual suggestions to Dora, who suspected her father of secretly offering her to Mr K in return for his wife (something Freud did not believe).

Freud concluded that her symptoms derived from jealousy. In other words, it was a classic Oedipal (or rather Electra) conflict: Dora was jealous of Mrs K and wished to replace her. Freud also suspected a great deal of ambivalence towards Mr K and a possible lesbian attraction to Mrs K.

Little Hans

Of all the case studies, this was perhaps the simplest and most successful. Hans was a 5-year-old boy who had developed such an intense fear of horses that he refused to leave the house in case one bit him. The phobia began after the birth of his little sister, when Hans was around three and a half. He was an intelligent, inquisitive child and her birth started him on a train of thoughts about where babies came from and the differences between male and female anatomy. Hans then became more and more interested in his penis and frightened that he would be castrated.

Again, this was an Oedipal conflict. Hans desired his mother and feared that his father would castrate him in revenge. Horses had come to symbolize his father. The fear of being bitten was in fact a fear of being castrated. In other words, he had displaced the fear of his father on to a fear of horses.

Freud later argued that children undergo a latency period in which the psychosexual stages of development, which take place between around 3 months and 5-years-old and culminate in the Oedipus conflict, are forgotten. Fourteen years later, Hans paid a visit to Freud. He could remember nothing of his phobia or his treatment.

The Rat Man

This was a case of obsessional neurosis, beginning in October 1907. The patient was a 29-year-old lawyer who had been drafted into the army. Freud saw him over an 11 month period and regarded the case as largely successful. The patient was later killed in the First World War.

The nickname ‘rat man’ came from the man’s obsession with a punishment used in Asia. An officer had described to him the way criminals were tortured by having rats burrow into their anus. The patient became obsessed by this and began to fear that such a punishment may befall his girlfriend and father. To prevent it, he developed a series of defences. For example, he saw a stone on the road down which his girlfriend was due to travel. He feared the carriage might run over the stone and crash, so he removed it, changed his mind, and then became obsessed with replacing it in the exact same spot.

Freud delved into his childhood and discovered the usual sexual explorations and fears of being punished for them by his father. There was also the common ambivalence towards the father figure: even after his father had died, the rat man would study until late then, at 1 a.m., the time his father often returned, he would go and look at his penis in the mirror, thus seeking both to please his father (by studying) and to defy him (by exposing himself). His obsessional neurosis was traced back to a fixation at the anal stage of psychosexual development. This would make sense since it is the stage overseen by the parents and characterized by sadistic urges (hence the obsession with the rat torture).

The rat man’s behavior made no sense because he was acting in response to the past. And this is key. As Freud famously put it, the neurotic repeats something from the past instead of remembering it. The punishment he claimed to fear for others was punishment he really feared for himself. He also revealed that as a child he had believed his parents could read his thoughts.

Of course, the Freudian case studies are vastly more complex than is suggested here. Reading them, you cannot help but be struck by the depth and complexity of the unconscious mind or the web in which the mentally ill are often caught.

The Wolf Man

Perhaps the most famous, and certainly the best, of Freud’s case studies is that of the so-called ‘Wolf Man’. The wolf man was in fact a wealthy, 23-year-old Russian. In many respects he was the most severely affected of all the cases, a man so neurotically ill he could barely dress himself. Treatment took place over a five year period, beginning in 1909, and was successful.